The Impact of Affirmative Action: A Comparative Analysis of MIT’s Demographics Before and After the 2027 Decision

Explore the changes in MIT’s demographics following the 2027 Supreme Court ruling that ended race-based affirmative action, and what it means for the future of diversity in higher education.

The 2028 admissions cycle at MIT marks a significant turning point, being the first full class to be admitted after the Supreme Court's landmark decision in 2027 that ended race-based affirmative action in U.S. college admissions.

The ruling has ignited nationwide discussions about diversity, equity, and access in higher education. In this blog post, we will compare the MIT Classes of 2024-2027 (pre-affirmative action ban) with the Class of 2028 (post-affirmative action). Through detailed analysis, we’ll explore how the ruling has affected various racial and socioeconomic groups, and we’ll examine the long-term implications for both MIT and the broader educational landscape.

Understanding Affirmative Action Pre-2027: An Overview

Before the 2027 Supreme Court ruling, affirmative action played a significant role in shaping the demographic makeup of many elite institutions, including MIT. By considering race as one factor in a holistic admissions process, MIT aimed to create a diverse student body that reflected a wide range of experiences, perspectives, and backgrounds. While test scores, academic achievements, and extracurricular activities remained central, affirmative action allowed MIT to proactively increase representation from underrepresented racial groups.

The data from MIT’s composite profile for the Classes of 2024-2027 illustrates how the institution utilized race-conscious admissions. According to the profile, the demographic breakdown among U.S. citizens and permanent residents was as follows:

- Asian American: 41%

- Black/African American: 13%

- Hispanic/Latino: 15%

- White/Caucasian: 38%

- American Indian/Alaskan Native: 2%

- Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander: 1%

MIT Class of 2028: Post-Affirmative Action

The 2028 admissions cycle was the first to occur after the ruling that ended race-based affirmative action. Given the significance of this change, there has been widespread interest in understanding its impact on the diversity of MIT’s incoming class.

Here is the breakdown of the MIT Class of 2028:

- Asian American: 47%

- Black/African American: 5%

- Hispanic/Latino: 11%

- White/Caucasian: 37%

- American Indian/Alaskan Native: 1%

- Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander: <1%

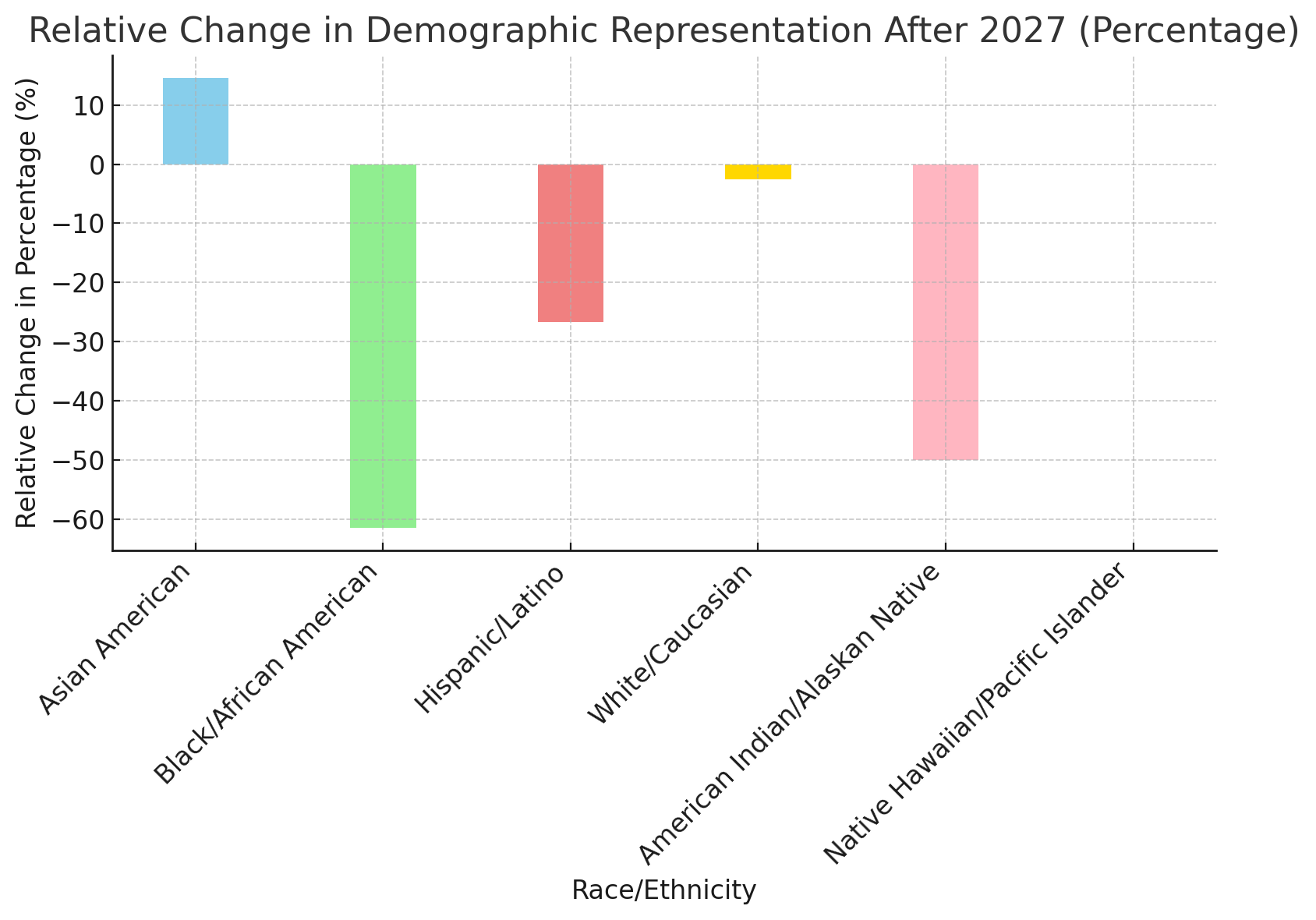

Analyzing the Data: Changes in Racial Representation

Asian American Students

One of the most notable changes between the pre-2027 and post-2028 periods is the increase in the percentage of Asian American students. From representing 41% of U.S. citizens and permanent residents in the Classes of 2024-2027, Asian Americans now constitute 47% of the Class of 2028. This 6% rise suggests that the removal of affirmative action may have benefited Asian American applicants, who were often overrepresented in applicant pools but faced admissions rates that didn’t always align with their academic performance.

Black/African American Students

The most significant decline occurred among Black/African American students. Their representation dropped from 13% in the Classes of 2024-2027 to just 5% in the Class of 2028.

Hispanic/Latino Students

Hispanic/Latino representation also declined, though less dramatically than Black representation. Hispanic/Latino students made up 15% of the Classes of 2024-2027 but only 11% of the Class of 2028.

White/Caucasian Students

The representation of White/Caucasian students remained relatively stable, with a slight decrease from 38% to 37%. This suggests that the removal of affirmative action did not significantly affect the percentage of White students at MIT, as other factors in the holistic admissions process may have played a more prominent role in shaping their admissions rates.

American Indian/Alaskan Native and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander

The percentage of American Indian/Alaskan Native and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander students saw minimal change. The representation of American Indian/Alaskan Native students fell from 2% to 1%, while Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander representation remained below 1%. These populations were already small and did not appear to be significantly impacted by the end of affirmative action.

What Is Going On?

Meritocracy and Academic Excellence

The primary reason behind the increase in Asian American representation lies in the metrics that now carry more weight in MIT's admissions process. Historically, Asian Americans have excelled in standardized testing and other academic measures. The removal of race as a consideration allowed these academic factors to dominate, leading to a significant boost in admissions for this group.

The "Bamboo Ceiling" and its Collapse

For many years, Asian Americans have faced what is colloquially known as the "bamboo ceiling" in higher education—a perceived cap on their representation in elite institutions due to affirmative action policies. With the end of these policies, the bamboo ceiling has effectively collapsed, allowing the full academic potential of this group to shine through in admissions.

Implications for Diversity

While Asian American students benefitted from this shift, the overall diversity at MIT has been affected. The decline in Black/African American and Hispanic/Latino students illustrates the trade-offs of moving toward a more academically focused admissions process. Though Asian Americans gained in the new system, the overall diversity of experiences, backgrounds, and perspectives may have diminished as the representation of historically underrepresented groups fell.

Sociocultural Factors and the Academic Pipeline

Many Asian American families place a strong emphasis on education, often encouraging their children to pursue rigorous academic courses, extracurricular activities, and test preparation from an early age. This cultural emphasis on education has resulted in a highly competitive applicant pool for elite universities like MIT. In a system that now weighs academic performance more heavily, it is no surprise that Asian American representation has surged.

A New Challenge for MIT

The dramatic increase in Asian American students also poses a challenge for MIT. While academic merit is critical, MIT has always placed a high value on diversity of thought and experience. The sharp decline in representation of other minority groups raises questions about how MIT can maintain a diverse learning environment.

Moving Forward

Moving forward, institutions like MIT may need to explore new ways to ensure a balanced and diverse student body. This could involve increasing outreach efforts to underserved communities, providing greater support for underrepresented minority students during the admissions process, or emphasizing other holistic factors like socioeconomic background, geographic diversity, and life experiences.

Want to see what kinds of students get admitted into MIT?

Explore our College Profiles Tool